CW: suicide, mental health problems, rape, sexual assault.

I have recently finished reading a biography of Lee McQueen by Andrew Wilson, Alexander McQueen: Blood Beneath the Skin. Published in 2015, it traces the designer’s life from childhood to his early death by suicide. My first encounter with McQueen was probably his iconic armadillo high heels popularised by Lady Gaga; I have a vague memory of watching her stagger across some screen I was watching, teetering impossibly high above dancers, throwing up her monster claws, her monstrosity and monstrous power seeming to thrum through her from the shoes themselves. Later, I took my mum to the McQueen retrospective at the V&A Savage Beauty; it’s the first time I remember feeling with my whole body the forceful power that clothes could have. Exquisitely curated and displayed, the exhibition was enormous as I remember it, going from McQueen’s graduate collection to his infamous bumsters to the model attacked by a mechanical arm spraying paint to Voss (2001), and on and on and on, ending in a giant cabinet of curiosities. This was a floor-to-ceiling construction with curios and details from throughout McQueen’s career, some boxes taken up by large LED screens showing highlights from his shows on a loop. The effect was dizzyingly overwhelming and I remember circling around the room several times with my neck craned all the way up to make sure I didn’t miss a thing.

Michelle Olley modelling in the final scene of McQueen’s 2001 collection Voss

I fell in love with the feeling that McQueen’s clothes gave me that day. I am not a fashion journalist or historian, so I don’t have anything particularly original to say about the clothes themselves or how they spoke to what had come before. But I can say that I was scared of his creations, they evoke a particular fear that is intoxicating. He upended what fashion could do and make you feel and what it symbolised; the women that walked down his runway were terrifying but also vulnerable; the women he dressed for red carpets and his friends that he made wedding dresses for were towering figures of fuck-you: Sarah Jessica Parker, Kate Moss, Lady Gaga. His shows were often criticised by fashion journalists for being misogynistic. In Highland Rape (1995), models walked down the catwalk with tartan and lace dresses ripped violently at the chest to expose their breasts. He was accused of using rape and violence as entertainment for the fashion world; in fact, McQueen was referencing the plunder of Scotland by the English in the Jacobite Rebellion and the Highland Clearances, and also reacting against the romantic way in which Scotland had been portrayed in fashion by designers like Vivienne Westwood (the two famously did not get on). McQueen painted fear and violence onto women’s bodies as a metaphor, but his clothes carried an immense power that was felt by anyone who wore them.

I don’t usually read biography, but I like how much they feel like an in-depth gossip with someone who knows absolutely everything about the subject of your gossip. Reading Blood Beneath the Skin, however, I felt myself becoming increasingly anxious. Lee McQueen had a torturous early life, suffering several counts of abuse as a child and teenager, which he never fully processed, taking his pain out in his clothes. The book goes into some grizzly detail, not about the abuse, but about how McQueen wrought his troubles on himself and on those around him, creating a noxious cloud of drink, drugs, excessive partying, controlling behaviour and an obsessive work ethic. It’s a stifling read, often bogged down in minute details that come together to form a picture of a man who didn’t know how to deal with what was done to him.

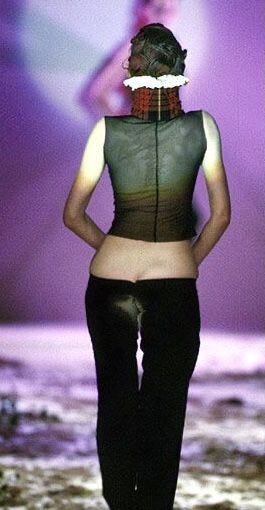

The infamous bumsters

Because I am a human and every piece of culture that I consume leads back to me, my brain bypassed everything I knew about McQueen’s suffering, and I got stuck on the sudden shift for McQueen from unknown pattern cutter on Savile Row to making splashes with his collections to designing for Givenchy and earning literal millions. After studying at Central St Martins, McQueen was putting his collections together on a shoestring, claiming dole and with some injections of cash from his muse and mentor Isabella Blow; his collections sold and received acclaim, but he earnt nothing and failed to pay collaborators for their work on the shows. But he kept doing it, and found his groove and a way to make it work financially, after a lot of reliance on use and exploitation, whether mutual or one-sided.

It’s embarrassing to hold myself up to Alexander McQueen, and I cringe as I write this. With my reading, the worm in my brain that likes to shame me thought: ‘you’re too good at being a cog in the machine. You’re too good at folding yourself at work to be creative. You’re too successful in capitalism to make your creativity work for you full-time.’ My new latent worry is that I am not risking enough for My Art™️, whatever My Art™️ is at the moment. I am simply too comfortable, not taking enough risks, not challenging myself enough, not precarious enough in my life to make anything worthwhile. Which is, of course, ridiculous. I voiced these concerns to T who swiftly and gracefully shut them down. Would you rather be you or Alexander McQueen, he asked me. Knowing what you do about his personal life and the cost of his success. Would you rather be him? Or course not, I demurred.

There are two things at play that I’m battling against with this one, intertwined but discrete. One is the myth of the starving artist, and the other is the myth of the tortured artist. The former says that you have to materially suffer in order to make your art, and the latter says that you have to psychologically suffer. These two things have directed the trajectory for how we conceptualise and treat creatives, though there has been a corrective movement over the last few years to dismantle their grip on our collective imaginations. Logically, I know that suffering does not de facto create good art, and my old friend Virginia Woolf wrote that what is needed in fact to be creative is not poverty but material comfort: a room and resources. Knowing this for others and knowing it for yourself, however, are different things entirely.

Shalom Harlow attacked by spray painting robots in No. 13 (1999)

McQueen would have made stunning clothes whether the abuse had happened to him or not, or he would have at least found some other outlet. It was not his trauma that defined his art or made him create, though the book itself reinforces this narrative to an extent by repeating at several intervals the idea that it all came out in his clothes. McQueen drew inspiration from such a wide variety of sources, from film to war photographers to history, that it is reductive to draw all of his collections back to his childhood trauma. It was also not his lack of money that made him successful, though it is absolutely true that material constraints bring about innovation because you are finding new ways to do things to skirt having to pay for the conventional way. But if a lack of funds is what defined McQueen’s creativity, on that logic his collections would have felt inflated and lacking in direction once he had a cash injection from investors. As this simply didn’t happen, I’m left to stick a pin in that ballooning lie that is inflating in my brain.

What directed his creativity was vision and discipline. These are what made his collections absolutely singular, not his initial lack of money in the industry or the trauma that he endured early in his life. Though he used his creativity as an avenue to explore these things, he was ultimately able to digest inspiration from everywhere and use it to power something that was entirely his own. He also spent years honing his skills in Saville Row and pattern cutting for other designers before he was granted a place on the Fashion Design MA course on the strength of his ability alone, as he had not previously attended university. He married incredible technical ability with an uncompromising tenacity and utter belief that he could do what he was setting out to do.

McQueen’s ending is a desperately sad one, and I had to ask T to kindly skim read the final pages and tell me when Wilson was done going into grizzly detail about exactly what police found when they found his body. I felt relieved when I finished the book, like someone had removed a great pressure from my chest; McQueen’s whirlwind was one of someone deeply traumatised and also deeply complicated. I am left with the silly comparisons between myself, an absolute nobody, and one of the greatest fashion geniuses of our time, and am grateful for the questions it has prompted. All this to say that McQueen was gone far too soon, and his legacy is one that changed fashion forever. I have never owned a piece of Alexander McQueen clothing but I found the pin badge that I bought at that V&A exhibition all those years ago. It is white with the decorative black skull that became his logo. It used to sit on my desk at home as I didn’t want to wear it for fear of being identified as someone that goes to one exhibition and makes it their whole personality. I salvaged the badge; I hope to one day know what it feels like to wear an Alexander McQueen piece, even if just for an hour. I imagine in that hour I would be the scariest, most savage version of myself. I can’t wait to meet them.